It is an overwhelming reality that in most cases of rape and sexual abuse, more than the perpetrator, it is the victim who feels an engulfing sense of shame.

It is thus entirely believable that Kirti Kulhari is not merely repeating the silent, stuttering Indu act of Indu Sarkar but is undergoing an unspeakably different trauma as Anu Chandra in Behind Closed Doors.

Ultimately, although it’s only Anu who’s in the dock for the murder of her husband, it’s three other marriages that also turn the searchlight inwards as the case unfolds.

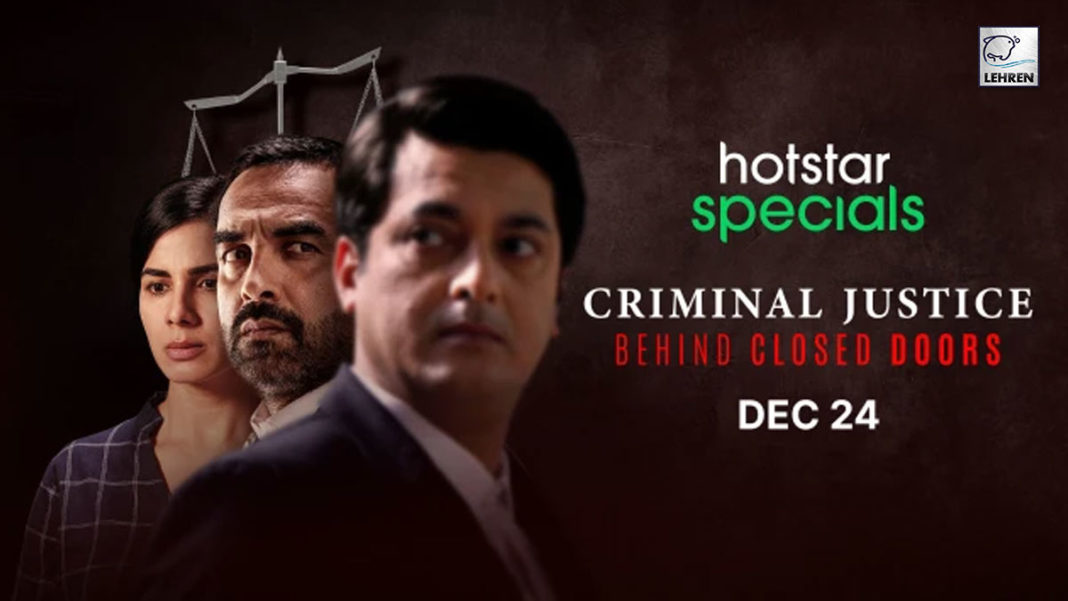

Adapted and written proficiently by Apurva Asrani from the British series Criminal Justice, Behind Closed Doors has Rohan Sippy and Arjun Mukherjee helming the episodes turn by turn.

The odds are stacked against Anu in what defence lawyer Madhav Mishra (Pankaj Tripathi) considers an open and shut case. But, to build Anu as the vulnerable victim, there is a sea of influential names on the opposite side. Well-connected mother-in-law Vijji Chandra (Deepti Naval). Hotshot legal brain Mandira Mathur (Mita Vashisht), so influential that she hires and fires public prosecutors. Supercilious, puja-offering prosecutor Dipen Prabhu (Ashish Vidhyarti) who’s not above a dirty trick or two to set up a media trial that today runs parallel to trials inside the courtroom. Ishani (Shilpa Shukla), an upper crust female prisoner with blow-dried hair who has the run of the jail and can be used by Mandira and Prabhu.

Above all, Public Prosecutor Bikram Chandra (Jisshu Sengupta), knifed by wife Anu, so renowned and widely liked that the legal community closes ranks.

So when the underdog wins, it is that much more of a triumph, with domestic abuse and the systematic chiseling of a wife’s self-esteem coming out of the bedroom and into the courtroom.

It gets a substantial boost with the irreplaceable presence of Pankaj Tripathi, the life of many a web series, who arrives as Madhav Mishra with mirth and more. Mishra’s marriage to Ratna in Patna provides a chuckle or two along with another layer of marital equations.

Nikhat Hussain (Anupriya Goenka) who slips into the defence team and her fierce jousting with a doormat mother throws the parents’ marriage also under the microscope.

Gauri (Kalyani Mulay) and Harsh Pradhan (Ajeet Singh Palawat) are an interesting husband-wife team at the police station whose relationship undergoes change as Anu’s case turns out to be not quite open and shut. The objectivity of senior cop Salian (Pankaj Saraswat) with an insider’s view of the vakil- and-vardi equation puts more life into the case.

While it is laudable to look closely at gender interconnections, you do pause to wonder why an educated woman like Anu who drives her own car, has a husband busy for long hours outside the house and has the bandwidth to have a fling with her therapist, had to be so meek, weak and vulnerable. In contrast is the less privileged lawyer’s wife Ratna who follows Mishra to Mumbai demanding her rights.

There are gritty sequences in jail, like a mother being separated from her child, that are moving. But there is the larger picture that must be considered. Is a jail the best place for a child? Especially when the mother has raised the child into treating regular visits to prison like a picnic with no remorse about a life of crime?

In places, it’s a convenient series where couples don’t lock their bedroom doors. Gauri and Harsh make love within the earshot of his mother which is for comic relief; Anu and Bikram have bedroom conversations and intimacy which can be seen and heard by their schoolgoing daughter which springs as relief for the defence in the courtroom.

There are other convenient spaces. Like Mishra’s wife Ratna being present in court just on the day when she can view the CCTV footage with her husband to explain what Anu dumped into the bin after the kill.

The justice-seeking clamour for gender sensitivity grows, as it should. But there is also a little voice that asks uncomfortably if gender tends to sometime override legalities. For instance, from the mother-in-law, the female cop and the female defence lawyer to the male lawyer’s wife and the lady magistrate, Anu’s abuse becomes so personal that the prosecuting counsel doesn’t make pertinent counters. Queries the counsel fails to ask: why did Anu put the knife through her husband only after she found out she was pregnant with another man’s child and not earlier? So did she kill him solely because of the sexual abuse or because she was also afraid of being caught out for adultery?

Apurva’s myriad characters mix bits of humour with a bit of legalese. But it’s gender relationships that are paramount in this murder and domestic abuse drama.